Striking a Balance: The Science Behind Riparian Buffer Rules for Cool Water and Fish Protection

Forest practices play a crucial role in maintaining the delicate balance between economic productivity and environmental conservation, particularly concerning water quality and the well-being of salmon streams. Recent scientific studies, namely the Hardrock and Softrock Experimental Buffer Treatment Studies, have shed light on the efficacy of current forest practices rules in keeping stream temperatures within acceptable limits for salmon habitats. This article explores the proposed rule changes based on scientific findings and the ensuing debate between forest landowners and the Department of Ecology.

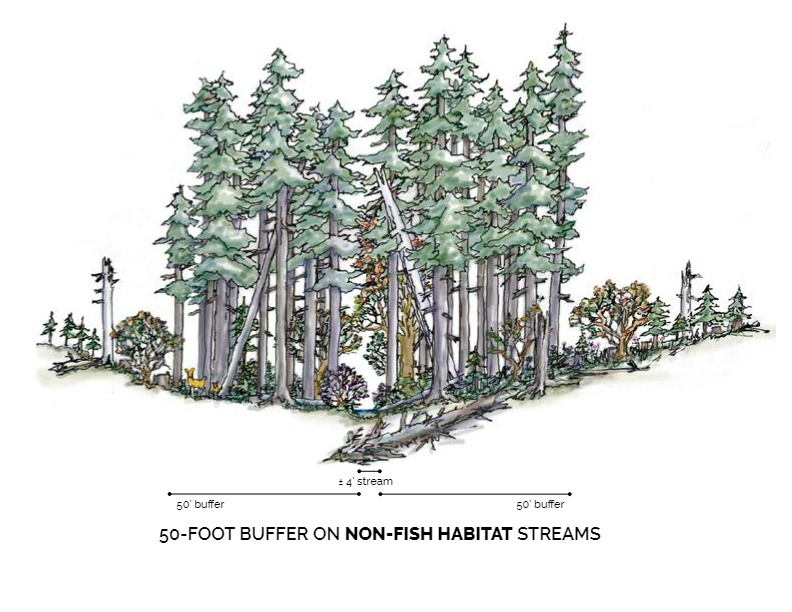

Scientific Backing: The Hardrock and Softrock studies reveal that existing forest practices keep both fish and non-fish stream temperatures below the Department of Ecology’s most common criteria for salmon streams, 16° Celsius (C). Despite concerns about potential temperature increases during timber harvesting, the studies show that such effects are relatively small and temporary, with streams naturally recovering as vegetation regrows. In response to these data, small, large, and county forest landowners propose rule adjustments, doubling the minimum length and widening buffers in critical areas along with widening the lower 500′ by 50%, to ensure the protection of fish-safe temperatures.

Dept. of Ecology’s Position: While the Department of Ecology acknowledges the temporary nature of temperature increases during timber harvesting, it aims to restrict any measurable change beyond 0.3°C in Tier II waters. This approach, attempting to minimize even minor changes in temperature, has sparked disagreement. Their proposed solution involves more than doubling the buffer area, length and width, along all non-fish streams in Western Washington. However, critics argue that the 0.3° C limit does not align with the natural variability seen in the Hardrock and Softrock studies, where background temperature variations can be 3°C or more, nor the plain language of the Antidegradation Policy.

Antidegradation Policy Misapplication: The Department of Ecology’s stance stems from a misapplication of the state’s Tier II antidegradation policy. Non-fish streams are all cooler than the required temperature criteria at 12-14°C, they are called Tier II waters. While Tier II allows for measurable changes if necessary and in the overriding public interest, to balance productive industries and water quality, the Department’s rigid interpretation seems to bypass the usual public input and alternatives analysis. Forest landowners stress that the Environmental Protection Agency never intended antidegradation to be a “no growth” rule but a policy enabling informed decisions balancing economic development and environmental protection, so long as the temperature does not exceed the stream criteria of 16°C.

Forest Practices Board’s Dilemma: Presented with experimental buffer treatment studies instead of long-term water quality monitoring, the Forest Practices Board faces critical decisions. The landowner proposal, emphasizing a nearly 49% increase in buffer area and foregone timber value, seeks a more measured response compared to the Department of Ecology’s proposal, which seeks a 140% increase in the buffer area. The absence of comprehensive, long-term water quality monitoring raises concerns about potentially overreacting to temporary temperature changes, especially in light of the anticipated impacts of climate change.

As the debate unfolds between forest landowners and the Department of Ecology, the need for a balanced approach that considers both economic interests and environmental benefit becomes increasingly evident. Scientific studies should guide rule changes, with a focus on adaptive management and long-term monitoring to ensure sustainable forest practices that protect water quality and salmon habitats without stifling economic growth. Striking this delicate balance is crucial for the well-being of Washington state’s forests and waterways.