WFPA advances policies that keep forests working, mills running, and rural communities strong.

WASHINGTON FOREST PROTECTION ASSOCIATION

Buffer Zones-Np Streams

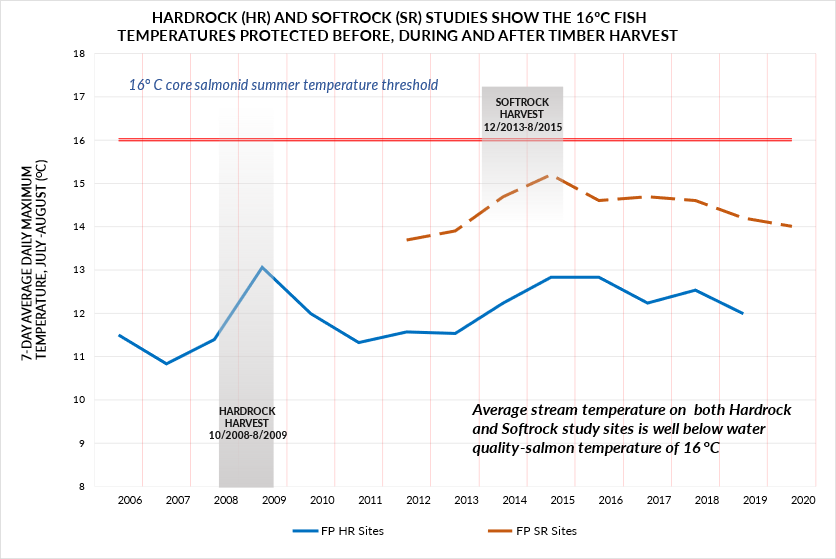

SCIENCE SHOWS Current RIPARIAN BUFFER RULES Keep Water Cool for Fish

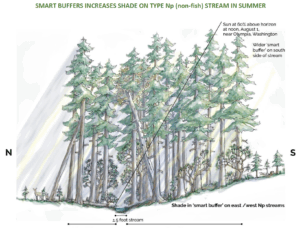

Adaptive management CMER science, as demonstrated in the Hardrock and Softrock Experimental Buffer Treatment Studies, shows that current forest practices rules maintain non-fish and fish stream temperatures below the Department of Ecology’s temperature criteria for salmon streams, specifically below 16 °C (60.8°F). Np streams are all cooler than that; at 12-14°C (54-58°F), they are classified as Tier II waters. Water Quality Standards enable the coexistence of productive industries and clean water, provided the temperature does not exceed the stream temperature criterion of 16°C.

LANDOWNERS PROPOSE TARGETED RULE CHANGES BASED ON SCIENCE

Small, large, and county forest landowners are proposing science-based improvements to current rules to further ensure fish-safe temperatures. The proposal builds on findings from Hardrock and Softrock studies showing timber harvest may cause a temporary temperature increase of 0.6–1.2°C (1.08–2.16°F), without exceeding salmon-safe thresholds. Streams naturally recover as vegetation regrows within a few years.

To strengthen protections, landowners propose:

- Doubling buffer lengths upstream of fish/non-fish intersections to at least 1,000 feet.

- Widening buffers to 75 feet on both sides of the stream for the first 500 feet.

These enhancements add precaution without unnecessarily burdening working forests.

DEPT. OF ECOLOGY’S OVERREACH: MISAPPLICATION OF tIER ii POLICY

The Department of Ecology is attempting to impose a strict 0.3°C (0.54°F) limit on any temperature change in Tier II streams, which is inconsistent with EPA-approved Tier II policies and Washington’s own rules. Tier II policy allows some degradation if it is necessary and serves an overriding public interest after an alternatives analysis and public input.

Ecology’s approach treats minor, temporary temperature shifts as prohibited, even though natural variation exceeds 0.3°C in many streams. This ignores nature’s reality and risks unnecessary restrictions on working forests.

Understanding Tier II: Protecting High-Quality Waters

Water Quality Standards consist of two parts: 1) designating beneficial uses and establishing criteria to protect them; and 2) an antidegradation policy and implementation process, which establishes three tiers of protection.

Washington’s Tier II Antidegradation Policy protects high-quality waters while allowing responsible development. The policy requires evaluating less degrading alternatives and weighing social and economic benefits before allowing any measurable change.

Tier II does not prohibit change. It requires a balanced decision, informed by science, public input, and coordination among government agencies.

Ecology staff agrees: Part of our job is to balance having productive industries and clean water.” “Also wanted to reiterate that WE DO allow degradation beyond measurable change – Tier II – so long as it meets the Overriding Public Interest test. Nov. 1, 2022

Forestry’s Water Pollution Control Program and Clean Water Act Assurances

Antidegradation is not a “no-growth” rule and was never designed or intended to be such. It is a policy that allows public decisions to be made on important environmental actions (EPA Water Quality Standards Handbook, Ch. 4 Antidegradation, EPA-823-B-12-002, 2012)

Washington’s Forests & Fish Law and Forest Practices Rules form a recognized Water Pollution Control Program under state water quality standards, certified by the federal Environmental Protection Agency. Forest practices operate similarly to general Clean Water Act permits and have passed Tier II tests through the issuance of a 50-year habitat conservation plan. Forestry is treated in a similar manner as a general point source NPDES* permit. Adaptive Management research shows that Best Management Practices (BMPs) used in forestry protect stream temperature (16°C) for aquatic uses. No additional TMDLs* or water clean-up plans are required for managed forest streams under the Forest Practices Act. The general NPDES permit and Water Pollution Control Programs are expected to pass the antidegradation test during the statement of benefits and costs of the social, economic, and environmental effects used to develop the general permit or program upon adoption, rather than requiring each action to be evaluated for compliance. (Mark Hicks, WQS_Temperature_Forestry 10/01/2018)

*Authorized by the Clean Water Act, the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit program controls water pollution by regulating point sources that discharge pollutants into waters of the United States. A Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) water clean-up plan sets a formal regulatory limit on heat pollution (temperature) to meet water quality standards.

Real-World Practices: Forest Stewardship and Buffer Protection

Today, forest landowners protect streams with buffers that maintain shade, control sediment, and safeguard habitat. These include 30′ no-equipment zones, 50′ buffers on half the stream length, extended protections near fish-bearing streams, sensitive sites and extra safeguards at unstable slopes. This resulte in actual stream buffering between 60-65% of Np streams to prevent water from warming to unsafe levels.

Monitoring confirms these rules are effective: Random site studies show 82–93% canopy closure and cool stream temperatures well below salmon standards.

Why We Need Monitoring, Not Overreaction

Instead of treating short-term changes as permanent, we should invest in landscape-scale water quality monitoring. The original Forests & Fish Agreement anticipated long-term tracking of forest stream health across the landscape, not just experimental studies.

Maintaining working forests while protecting water quality ensures economic and environmental resilience for future generations.

THE EXPERIMENTAL BUFFER TREATMENT STUDIES CLEAR-CUT ENTIRE NP BASINS TO ISOLATE THE IMPACT OF FOUR BUFFER TREATMENTS.

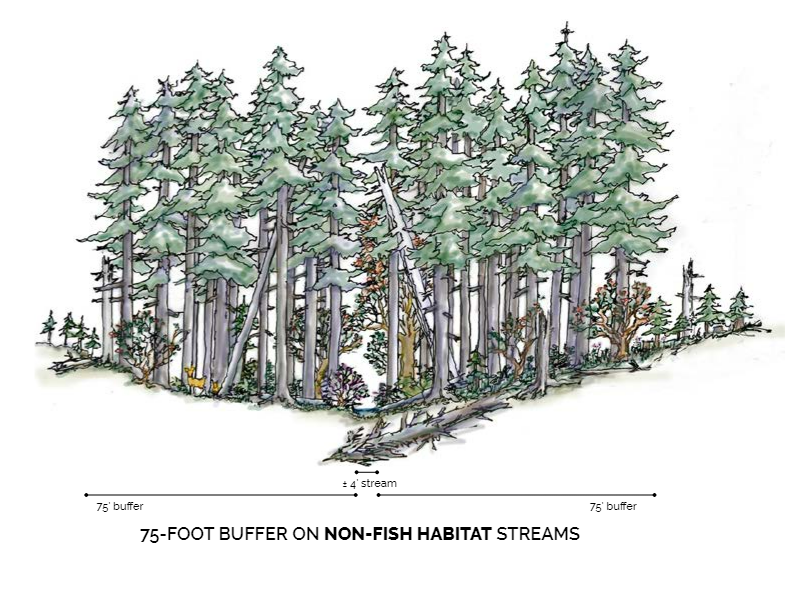

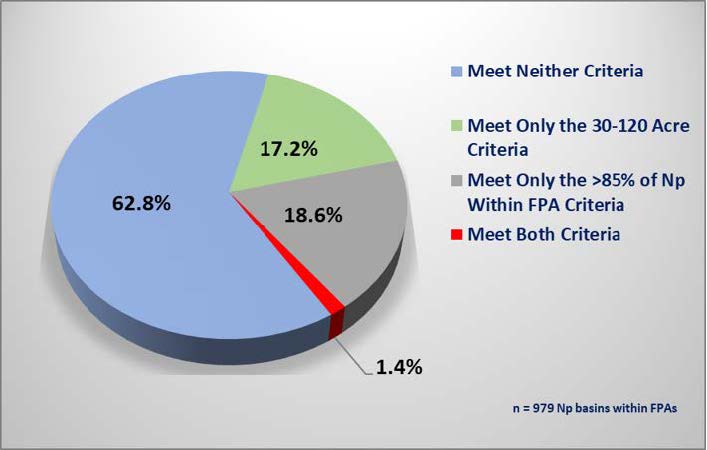

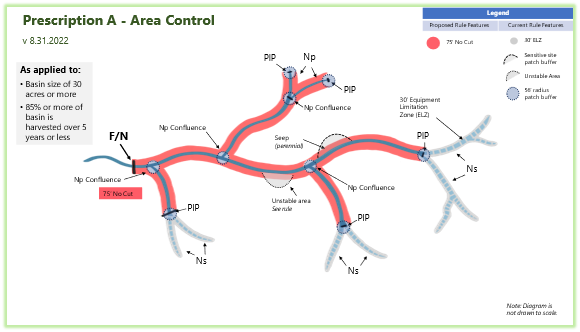

The studies focused on the temperature response of clear-cutting an entire Np basin between 30-120 acres and measuring the post-harvest temperature and amphibian abundance changes. This does not reflect actual timber harvest patterns in the field. A Before-After Control-Impact study design was used to assess the response of temperature, nutrients, drift, sediment, streamflow, shade, and litterfall to three buffer treatments and unharvested controls. However, harvesting an entire Np basin in one entry is a more intensive harvest pattern than forest managers do in the real world. This harvesting pattern is not typical of what happens in the field. The safeguard if an entire basin is harvested within 5 years is to leave 75-foot buffers on each side of non-fish (Np) stream to protect the watershed. This only occurs 1.4% of the time however.

THE HCP AND BIOLOGICAL OPINION OF USFWS AND NMFS ANTICIPATED SMALL AND ISOLATED TEMPERATURE INCREASES IN NP STREAMS.

The federal US Fish and Wildlife and National Marine Fisheries Services that approved the 50-year Forests & Fish Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) anticipated temporary temperature changes post-harvest and rapid recovery after growth. On the other hand, the State Dept. of Ecology’s standard of no change > 0.3°C anywhere, anytime is inconsistent with the larger HCP vision.

The federal services recognized that temporary increases in stream temperatures recover within 5-15 years to pre-harvest conditions.(FP HCP Chapter 4d pgs. 239-241) Forest management over 40–60-year rotations do not create persistent and permanent change in water temperature, in fact on average minor temperature response measured in the Softrock and Hardrock studies (0.6 and 1.2°C respectively) occurs over a relatively short period of time (3-9 years) compared to a harvest rotation of 40-60 years. When considering these findings in addition to other relevant CMER and non CMER studies, we believe the landowner and county’s proposal addresses the problem identified. (see also NMFP BiOp page 285 and USFWS BiOp page 5 and 862)

FISH AND NON-FISH TEMPERATURES ARE PROTECTED UNDER CURRENT FOREST PRACTICES RULES.

Temperature response post-harvest and amphibian abundance changes measured eight to nine years post-harvest are the two primary areas of concern. While there has been great focus on the measurable change temperature criteria in non-fish streams of greater than 0.3° C, there has been little to no acknowledgement that most Hardrock and Softrock treatment sites were well below the 16° C designated use temperature standard both before and after harvest. All Forest Practices treatment sites in the Hardrock and most Softrock sites study were below this standard. This is great news!

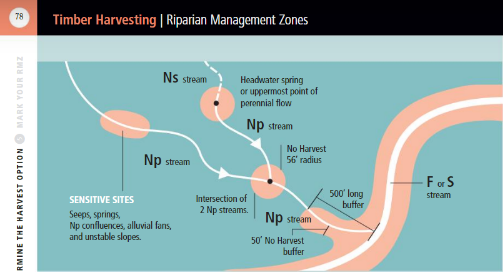

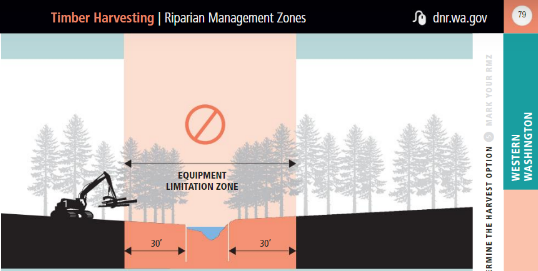

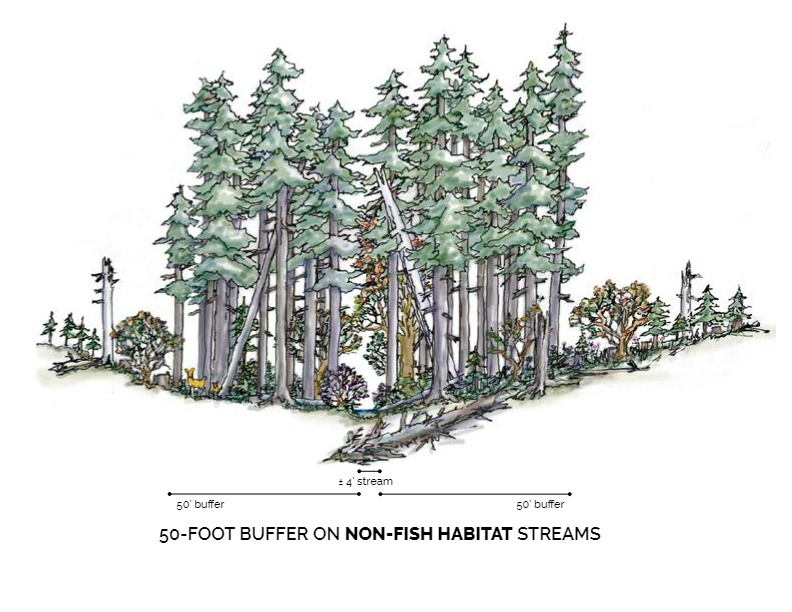

Current Np rules maintain shade by limiting timber harvest near Np streams.

Landowners must maintain a continuous 30’ equipment limitation zone along the entire Np stream length and maintain a minimum of half of the stream length with 50’ buffers along both sides of the stream to prevent water from warming to unsafe levels.

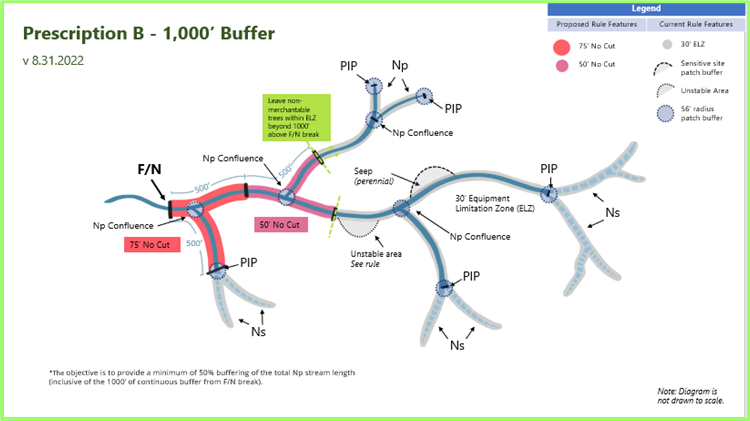

Current rules also require a minimum of 300-500’ of buffer length upstream of the intersection where non-fish and fish streams meet, and protecting sensitive sites such as Np stream junctions, seeps, springs, and the Np stream initiation points with 56′ radius buffers. The objective is to provide a minimum of 50% buffering of the total Np stream length.

Buffers are also provided where there are potentially unstable slopes along Np streams. The studies show that with this extra protection, the actual length of Np streams buffered under current forest practices requirements likely averages 60% – 65% rather than the minimum 50%.

SMALL AND LARGE LANDOWNER AND COUNTY TYPE NP PROPOSAL.

The small/LARGE landowner and County Np buffer proposal is a two-component prescription for Western Washington (WWA) Np streams and includes a small landowner option.

Timber harvest of an entire Np watershed greater than 30 acres would require 100% of the Np stream to be protected with 75’ buffers on both sides of the stream – this is the treatment tested in the Experimental Buffer Studies. To recognize stakeholder concerns about multiple entries, the proposal is if 85% of the entire basin is harvested within 5-years, the 75′ continuous buffer is required.

A 75′ buffer of trees on each side of the stream is left for the first 500′, then a 50′ buffer for the next 500′ for a minimum total of 1,000′ from the intersection of Fish/Non-fish streams to protect the transition zone and ensure cool water for fish. Most Np streams are less than 1,300 feet.

Beyond the 1,000′ buffer of trees, 56′ radius patch buffers would be required on sensitive sites (e.g. stream junctions, springs, seeps) and the origin of the stream, the perennial initiation point (PIP). Existing unstable slopes rules would also apply, as necessary.

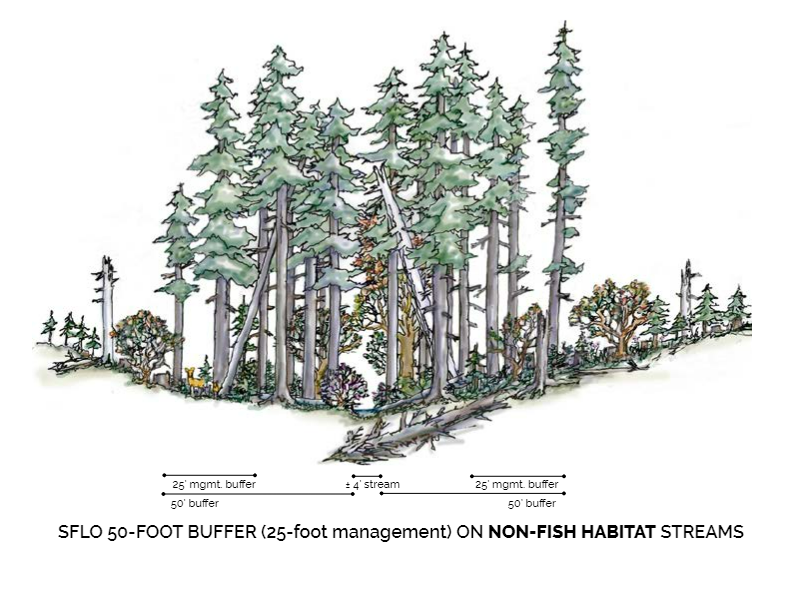

The small forest landowner option is the same as prescription A and B except the buffer width is 50 feet and includes a management option in the outer 25 feet. This option recognizes the disproportionate economic impact to small landowners from substantive regulatory changes.

It also acknowledges small forest landowners tend to have smaller harvest units and harvest less often than large landowners. Incentivizing forest landowners to remain on the landscape, managing their forests for multiple benefits, should be a policy priority for the FPB and the State of Washington.

Private Foresters Follow the Forests & Fish Law

During timber harvesting, buffers of trees and vegetation are protected next to streams, called riparian zones, to protect stream habitat for amphibians and native fish, especially salmon and trout. Protection for buffers are part of the requirements set forth in the Forests & Fish Law and Forest Practices Regulations to protect cool water temperatures and reduce silt from entering streams keeping water clean. The law set in motion one of the largest Habitat Conservation Plans in the nation, which is a contract between the State of Washington and US Fish and Wildlife and National Marine Fisheries Services to protect fish habitat on all non-federal forests for 50-years. Buffers of trees are maintained across 9.3 million acres of Washington’s working forests along side 52,000 miles of streams on the westside and 8,000 miles of streams on the eastside of the Cascades.

From 2001 through 2021, forest landowners, including the Green Diamond HCP have removed nearly 9,200 barriers to fish passage. To date, 100% of the barriers identified have been eliminated, opening nearly 6,500 miles of historic fish habitat. This success has been achieved through investments by the state, small and large private landowners of $390 million—of which private forest landowners have contributed $265 million for road improvements through 2021. Learn more at ForestsandFish.com.

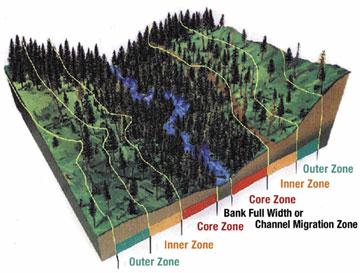

Different Types of Buffer Zones ON FISH HABITAT STREAMS

When forest landowners negotiated Forests & Fish, they knew it would mean leaving more trees near the stream to provide protection for fish, water, amphibians, and other wildlife species; and they wanted to provide that protection. Negotiations resulted in larger buffers and emergency rules went into effect in 1999. There are three buffer zones that are determined by site-class, stream width and habitat type and to put protection where it is most needed — closest to the stream. Westside buffer widths are 90-200 feet with a core “no-harvest” zone = 50 feet. Eastside buffer widths are 75-130 feet with a core “no-harvest” zone = 30 feet.

Core Zone

The Core Zone is a no-touch buffer that extends outward from the stream for 50′ on the westside and 30′ on the eastside of the Cascades.

Inner Zone

The Inner Zone (beginning at the edge of the Core Zone) can be managed to allow sufficient growth for healthy riparian areas.

outer Zone

Management activities in the Outer Zone are dependent on many complex factors and are dependent on what management occurred in the inner zone.

The buffers are designed to work together to provide protection for aquatic resources and be as economical as possible for forest landowners.

Learn More About Managing the Health of a Working Forest